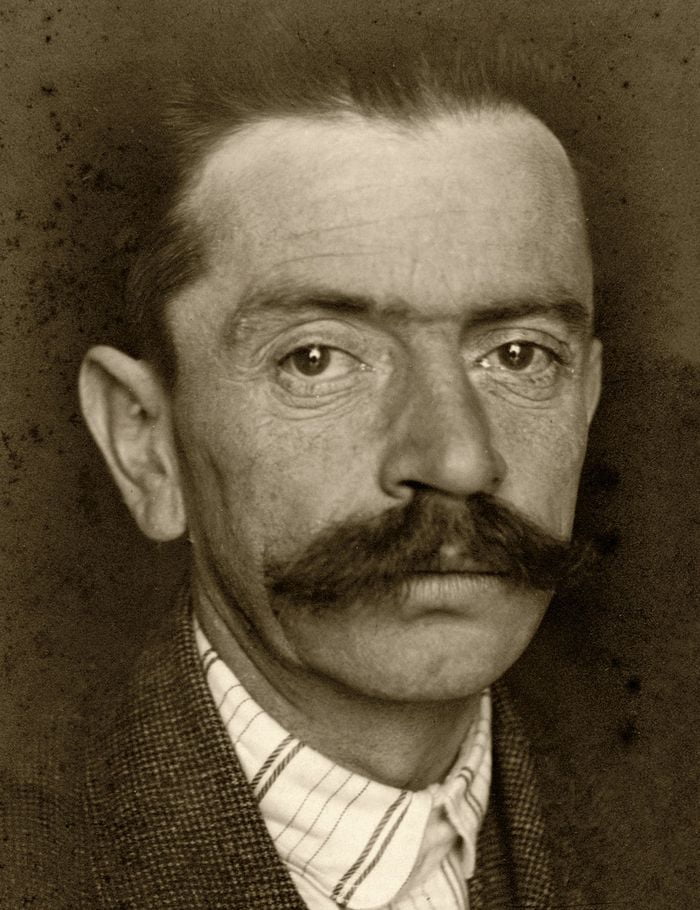

Ivan Cankar (18—?—1919)

Cankar was one of the most promising of the younger group of Slovenian writers. He had established a solid reputation as novelist, dramatist, and writer of short stories. His most significant work was produced late in his life. The volume, Dream Visions, from which Children and Old Folk is selected, appeared in 1917.

This story is here published for the first time in English. The translation is by Helen P. Hlacha.

Children and Old Folk

Each night, before they went to bed, the children used to chat together. Seating themselves on the ledge of the broad oven, they uttered whatever came into their minds. Through the dim window the evening twilight peered into the room with dream-laden eyes. Out of every corner the silent shadows drifted upwards, carrying strange stories with them.

They spoke of whatever came to their minds, but to their minds came only pleasant stories of sunlight and warmth interwoven with love and hope. The whole future was one long bright holiday; no Lent, between Christmas and Easter tide. Over there, somewhere behind the flowered curtain, all life, blinking and throbbing, silently poured from the light into light. Words were whispered and only half understood. No story had any beginning, nor definite form. No story had an end. At times all four children spoke at once, yet none confused the other. All gazed enthralled into a beauteous heavenly light where each word was clear and true, where each story had a clear and living face, and each tale its glorious finish.

Introspective eyes

The children bore so marked a resemblance to one another that in the dim twilight the face of the youngest, four-year-old Tonchek, could not be distinguished from that of the ten-year-old Loizka, the eldest. All had thin, narrow faces and large, wide-open eyes—introspective eyes.

That evening, something unknown from an unknown place reached with violent hand into that heavenly light and struck pitilessly among the holidays, the stories, and legends. The post had brought tidings that the father “had fallen” on Italian soil. Something unknown, new, strange, entirely incomprehensible rose before them. It stood there, tall and broad, but had neither face, nor eyes, nor mouth. Nowhere did it belong, not to that clamorous life before the church and on the street, nor to that warm twilight around the oven, nor to the stories.

It was nothing joyful, but neither was it particularly sorrowful, for it was dead; because it had no eyes that it might by their look reveal wherefore and whence, and no mouth that it might explain by words. Thought stood humbly and timidly before that enormous apparition as before a great black wall, motionless. It approached the wall, and stared dumb and ponderous.

“But when will he come back?” asked Tonchek, wonderingly.

Loizka nudged him with an angry look. “How can he come back if he has fallen?”

All lapsed into silence. They stood before that great black wall, and beyond it they could not see.

“I`m going to war, too!” unexpectedly announced seven-year-old Matiche, as if he had swiftly hit up the right thought. That was evidently all that it was necessary to say.

“You`re too small,” admonished four-year-old Tonchek in a deep voice. Tonchek still wore dresses!

Thinnest and Sickliest

Milka, the thinnest and sickliest of them, who was wrapped in her mother`s large shawl and resembled a wayfarer`s pack, asked in her soft little voice from somewhere out of the shadows, “What is war like? Tell us, Matiche, tell us that story!”

Matiche explained, “Well, war is like this. People stab each other with knives, cut each other down with swords, and shoot each other with guns. The more you stab and cut down, the better it is. Nobody says anything to you, `cause that`s how it has to be. That`s war.”

“But why do they stab and cut each other down?” Milka insisted.

“For the Emperor!” said Matiche, and all were silent.

In the dim distance before their clouded eyes appeared something mighty, glistening with the radiance of glory. They sat motionless, their breaths barely daring to escape their mouths, as in church at the benediction.

Then Matiche again swiftly gathered his thoughts; possibly just to dispel the silence which lay so heavy over them. “I`m going to war, too. Against the enemy.”

“What is the enemy like? Has he horns?” suddenly inquired the thin voice of Milka.

“`Course he has, else how could he be the enemy?” seriously, almost angrily replied Tonchek in emphatic tones. And now not even Matiche himself knew the correct answer.

“I don`t think he has them!” he said slowly, haltingly.

“How can he have horns? He`s a person like us,” voiced Loizka unwillingly. Then, reconsidering, she added, “Only he has no soul.`

After a lengthy pause Tonchek inquired, “But how does a person fall in the war? Like this, backward?” And he illustrated the point.

“They kill him to death!” calmly explained Matiche.

“Father promised to bring me a gun.”

“How can he bring you a gun if he has fallen?” Loizka roughly re

“To death.”

Through the youthful and wide-open eyes silence and sorrow stared into darkness, into something unknown, to heart and mind inconceivable.

Grown hoarse

At the same time on a bench before the cottage sat the grandfather and grandmother. The last red rays of the sun glowed through the dark foliage in the garden. The evening was silent except for a smothered, prolonged sob, already grown hoarse, which came from the stable. In all probability it was the wail of the young mother who had gone there to tend the livestock.

The two old people sat deeply bowed, close to one another, and held each other`s hands as they had not done for a long time.

Read More about Veliko Tarnovo – legends and reality